Degradation is now affecting a larger area than deforestation. When all of its drivers and potential overlaps are considered, the estimated total degraded area increases to 2.5 million km², which represents 38% of the remaining Amazon rainforest.

The Amazon is a critical component of the Earth’s climate, and Brazil and the planet are fighting to reduce tropical deforestation. But we have another hidden enemy: forest degradation. Two different issues cause degradation:

- the weakening of the ecosystem due to deforestation and socio-economic activities that are causing damage to the forest health;

- the increase in global temperature and the reduction in precipitation in the Amazon region. Two recent works in Science magazine discuss these aspects (Lapola et al., Science 379 and Albert et al., Science 379).

Among such forest damages, the most important are edge effects (due to deforestation and consequent habitat fragmentation), logging, the opening of roads, and the impact of fires, among others. Data analysis on the extent of fire, edge effects, and timber extraction between 2001 and 2018 reveals that 0.36 million km2 (5.5%) of the Amazon Forest is under some form of degradation, corresponding to 112% of the total area deforested in that period.

Degradation is already affecting a larger area than deforestation. The estimated carbon loss from these forest disturbances is comparable to carbon loss from deforestation. Ongoing tree mortality after disturbance means that forests can continue to emit more carbon for decades after the disturbance. Disturbances can bring about as much biodiversity loss as deforestation itself, and forests degraded by fire and timber extraction can have up to 34% reduction in dry-season evapotranspiration. Biodiversity loss and ecosystem functioning are other relevant aspects of forest degradation.

Degradation is already affecting a larger area than deforestation. The estimated carbon loss from these forest disturbances is comparable to carbon loss from deforestation.

Paulo Artaxo

The scale of the forest degradation impact when all the drivers are taken into account and all possible overlaps between them, the estimate of the total degraded area increases to 2.5 millions km2 or 38% of the remaining Amazonian forests. Brazil certainly has to take a closer look at forest degradation.

The second component of forest degradation is the impact of global climate change in Amazonia. In large areas of Amazonia, average temperature increases already reach 2 °Celsius, which is twice the global average increase. And precipitation in some regions already shows significant reductions. The climate extremes such as extensive droughts and floods are on the rise.

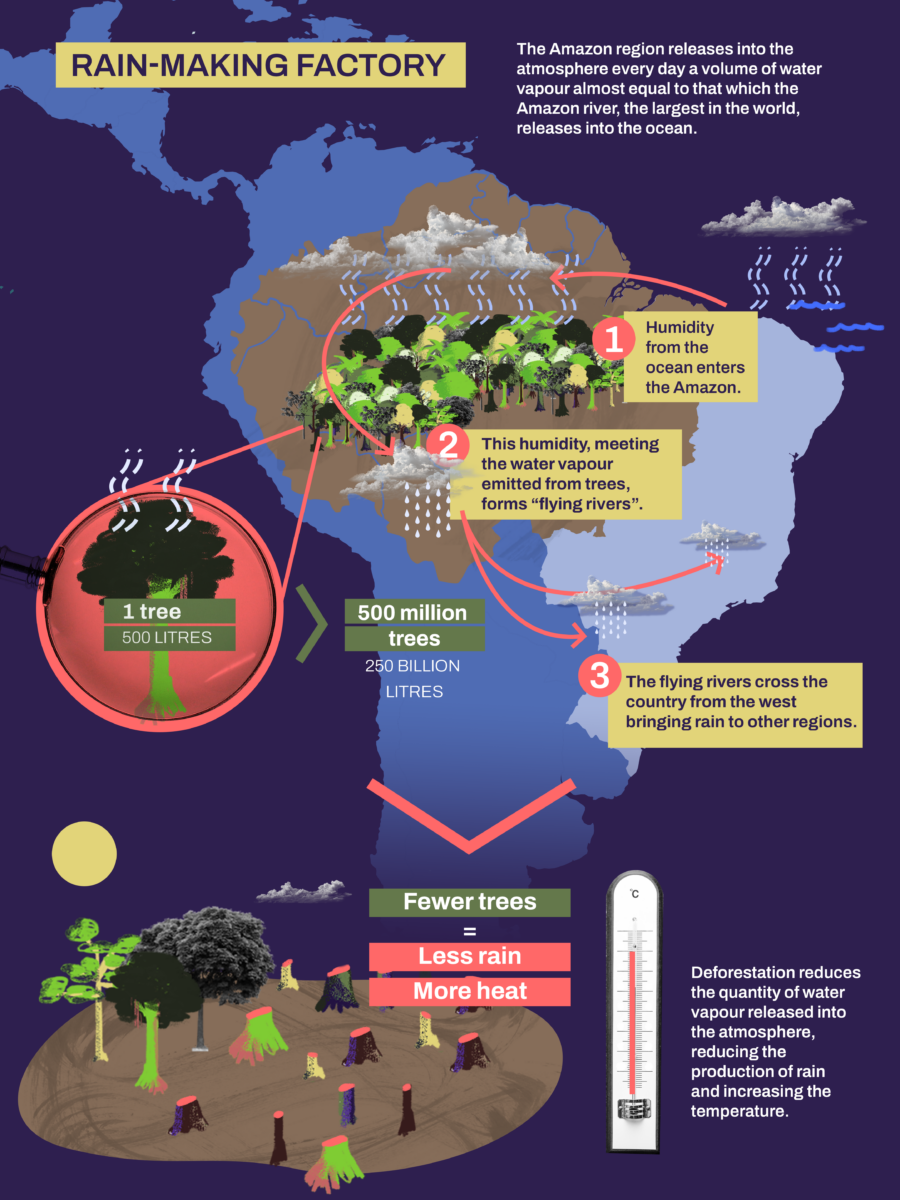

In Amazonia, forest-rainfall feedback is required to maintain the current forest cover. About half of the precipitation over the Amazon is recycled from evapotranspiration, and Amazonian forest cover buffers the ecosystem against variations in rainfall and fire. Portions of the southern and eastern Amazon are changing to a disturbance-dominated regime. This is important for a tropical forest that settled under a rather stable climate over the Holocene.

In terms of the future, the projections from the latest IPCC report show that at the current pace, average global temperatures can increase by 3 °Celsius, which can bring a hotter Amazonia by about 4 to 4.5 °Celsius. This is a large climate change in the ecosystem that is already underway. Recent papers show that parts of Amazonia are losing carbon to the atmosphere, indicating that some regions have already transitioned, with forest respiration and burning outpacing forest photosynthesis. We must globally end the use of fossil fuels to avoid such scenarios.

Even if Brazil fulfills its Paris Agreement commitment (zero deforestation by 2030), forest degradation will remain a dominant source of carbon emissions independent of deforestation rates. Preventing further deforestation remains crucial for stabilizing the climate system, preserving biodiversity, and ensuring sustainable development.

Deforestation is a primary driver of greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss and a driver of several forms of forest degradation. The integrity of the Amazon depends on maintaining sufficient forest cover. Preventing additional degradation will also benefit from the conditions required to curb deforestation, such as strengthening land tenure, environment-oriented credit concession, and providing sustainable income and livelihood alternatives that can attenuate social inequalities.

Preventing additional degradation will also benefit from the conditions required to curb deforestation, such as strengthening land tenure, environment-oriented credit concession, and providing sustainable income and livelihood alternatives that can attenuate social inequalities.

Paulo Artaxo

The central message is that human activities are rapidly degrading Amazonian environments, posing a threat to the region’s vast biodiversity reserves and critical ecosystem services on a global scale. To effectively address this degradation, policies must integrate efforts to combat deforestation and include innovative measures targeting the various disturbances contributing to the problem. Achieving this goal will require engaging with the wide range of actors involved in causing degradation, implementing effective monitoring of different disturbances, and refining policy frameworks.

These efforts will be bolstered by rapid and multidisciplinary advancements in our understanding of the socioenvironmental factors that drive tropical forest degradation. We also need to globally eliminate fossil fuel emissions. Ultimately, this knowledge will provide a solid foundation for developing effective policies and programs to curb the degradation of Amazonian environments.

The opinions expressed in this article are the writer’s own.