Although forest regrowth in the Brazilian Amazon covers a vast area, it is invisible to existing monitoring systems. Without monitoring, regrowth remains dangerously vulnerable.

As expected, president Jair Bolsonaro’s recent meeting with billionaire Elon Musk was no more than a ploy to carve out space in the media. Still, the sheer hypocrisy of one of the alleged reasons for the meeting cannot go unnoticed: to discuss a satellite-based monitoring system for fighting deforestation in the Amazon.

For someone who takes environmental monitoring seriously and considers it a critical tool for protecting the Amazon Forest, it’s offensive to see the current federal administration feign interest in the topic. This is the same government that systematically dismantled environmental control in the region and helped push Amazon deforestation to what is now the worst levels of forest loss seen over the past 15 years.

It’s worth stressing that Brazil already has exceptional systems for remote forest monitoring in the Amazon: Prodes has been in operation for over three decades, and Deter since 2004. The former annually maps deforested areas, while the latter identifies forest loss hotspots in near-real-time and issues associated alerts to support environmental control operations.

Developed by the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe), both were pioneering systems when launched and have seen improvements over time. Prodes and Deter have been rigorously validated and are widely supported across national and international scientific communities.

No system is perfect or infallible, of course, but Brazil faces no shortage of satellite imagery to fight Amazon deforestation. The relevant bottleneck is environmental authorities’ capacity to provide a binding response, which the current federal administration has actively sought to obstruct.

In 2014, secondary vegetation covered nearly a quarter of the area that had been historically cleared in the region. This totalled almost 17 million hectares of forest regrowth, mostly from passive regeneration.

Here’s a suggestion for an administration that is genuinely interested in using satellites to strengthen the protection of native vegetation: support the development of systems for mapping and monitoring secondary vegetation in the Amazon.

Secondary vegetation grows in areas that have already been deforested. In 2014, the latest year with official data on land use within deforested areas in the Amazon, secondary vegetation covered nearly a quarter of the area that had been historically cleared in the region. This totalled almost 17 million hectares of forest regrowth, mostly from passive regeneration. These are largely abandoned areas in which forest regrowth occurs naturally, without the support of active restoration efforts.

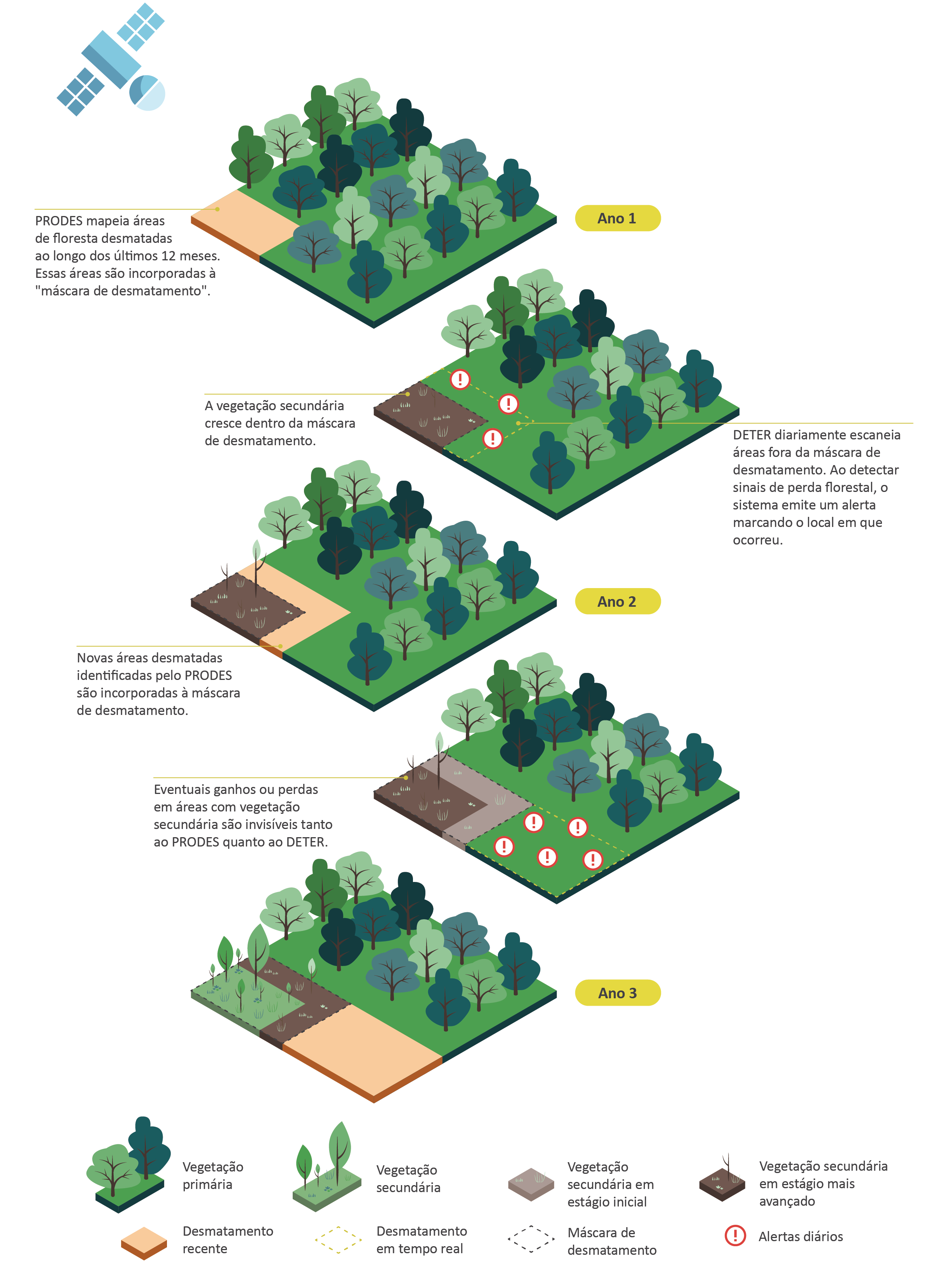

Secondary vegetation in the Amazon is completely vulnerable, because it is invisible to existing monitoring systems. Both Prodes and Deter were designed to detect exclusively the loss of primary vegetation that has never been deforested. The systems don’t even look into the “deforestation mask”, which comprises the entire area that has been historically cleared and is precisely where secondary vegetation grows. The figure illustrates this relationship.

Why is secondary vegetation invisible to forest monitoring systems?

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio (2020).

For a while, Brazil mapped secondary vegetation in the Amazon as part of the TerraClass Project, which classified land use in deforested areas. However, the project was discontinued and 2014 is the latest year for which data are available.

Efforts in academia and civil society have extended this mapping for longer periods and revealed that, within the past decade, the clearing of secondary vegetation has exceeded that of primary vegetation.

Systems that are developed and maintained by civil society, such as that offered by the MapBiomas project, are crucial to promote transparency and accountability. However, they do not eliminate the need for an official governmental system for monitoring secondary vegetation that ensures methodological consistency across official Brazilian data on Amazon forest cover.

What is missing is political support from an administration truly committed to strengthening forest protection in the Amazon.

Without official data and without regular and frequent monitoring, Brazil cannot measure its secondary vegetation, let alone protect it. These are important gaps considering that tracking and protecting these areas are critical to Brazil’s capacity to prove compliance with its greenhouse gas reduction commitments and to monitor compliance with Forest Code restoration requirements.The development of systems for monitoring secondary vegetation is not without some technical challenges, but it is perfectly feasible.

Brazil has access to the technical capacity that is needed to meet these challenges and, even without Musk’s satellites, the country could set these systems up relatively quickly and cheaply. What is missing is political support from an administration truly committed to strengthening forest protection in the Amazon.

The opinion articles are the author’s own responsibility.