Disputes for mineral resources are known to be violent. Public policies must stop ignoring this.

Artisanal mining (garimpo, in Portuguese) covers more than half the mining area in Brazil, according to MapBiomas. This activity is particularly important in the Amazon biome, which accounts for 94% of the area occupied by artisanal mining in the country – and among these 87% are used for gold mining.

Despite its inherent potential to generate wealth, mining and artisanal mining are usually associated with violence. This may sound familiar and bring memories of countless Western movies depicting bloody disputes for gold; or the role of Blood Diamonds in fueling wars in West African countries; or, closer to our home, the Serra Pelada massacre.

Indeed, mineral resources can be a curse instead of a blessing. On the one hand, these resources can bring more income and jobs to local communities – a blessing. On the other hand, the prospect of wealth can fuel disputes between groups that wish to control mineral deposits, which often culminate in armed conflict and escalating violence in the region – a curse.

Several studies document these negative consequences. A research paper published in the American Economic Review shows that price increases of multiple minerals led to more violence and conflict between rebel groups precisely where the deposits of each mineral are located. Something similar also happened in Colombia, where disputes for gold deposits are driven by drug cartels. The idea behind these phenomena is that, as the value of minerals increases, armed groups become more willing to fight for them despite the underlying risks.

Considering these facts, it is shocking that in Brazil the link between mining, violence, and paramilitary groups is largely ignored when discussing new laws and public policies. This is especially problematic in the Amazon, where not only is illegal mining associated to other environmental crimes, according to a report by Instituto Igarapé, but it also enables money laundering for other criminal activities.

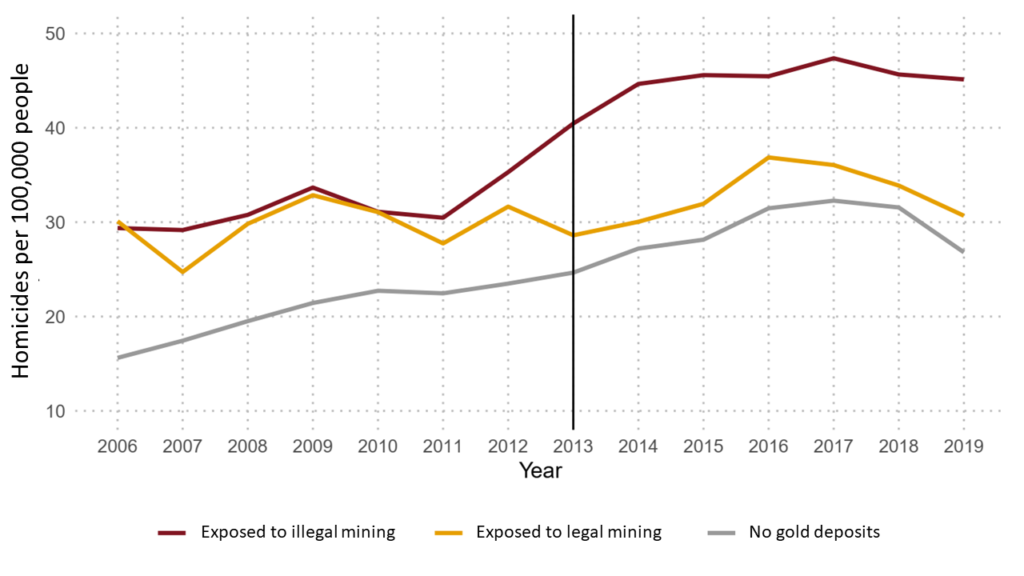

A report about violence in the Amazon produced by researchers at Insper and Climate Policy Initiative/PUC-Rio for the Amazônia 2030 Project investigates some of the social impacts related to mining. Data reveal a sharp increase in homicide rates in municipalities exposed to mining in general and illegal mining in particular.

The social impact of mining, however, is still not present in the public debate about this sector. The case of Medida Provisória 610/2013 is a clear example of how violence in artisanal mining sites in the Amazon is often neglected. Even though the original bill had nothing to do with mining, a handful of articles regulating this sector were introduced at the last minute before it was passed as Law 12.844/2013. These articles essentially exempted buyers from punishment when acquiring illegal raw gold from artisanal miners.

As explained in a report by Ministério Público Federal, in practice this allowed official gold buyers – known as Pontos de Compra de Ouro (PCOs) – to buy illegally explored gold without consequences. This made it much easier for illegal miners to “launder” illegally mined gold, because once they sold it to PCOs, the mineral immediately became legal. Hence, the official gold buyers became official gold laundering stores.

Easy access to gold laundering in turn stimulated the illegal mining activity. And illegal mining sites are typically very violent. This is attributable not only to the proximity between illegal gold mining and drug cartels, but also to the fact that territorial disputes in the Amazon are often solved with violence, not legal institutions.

A paper by researchers at Climate Policy Initiative/PUC-Rio was the first to analyze the effect of this new regulation on violence in the Amazon. The study shows that the stimulus given to illegal mining caused a 20% increase in homicide rates in places where gold was produced illegally. Specifically, approximately 1,300 lives were lost in the Brazilian Legal Amazon due to weakening the enforcement against illegal transactions of gold between 2013 and 2019.

Figure 1 shows one of the results in the paper. Indeed, municipalities more exposed to illegal gold mining observed a significant increase in violence precisely after the approval of Law 12.844/2013. The same does not happen in areas of legal mining or without gold deposits. This suggests that favoring illegal mining contributed to the increase in violence associated with this activity.

Figure 1: Homicide Rate in municipalities of the Brazilian Legal Amazon according to their exposure to legal or illegal gold mining

Source: Pereira and Pucci (2021) with data from DataSUS, Serviço Geológico Brasileiro and IBGE.

Nonetheless, even though this tragedy could have been partially averted based on the knowledge about the relationship between mining and violence, this possibility was not given much space during the debate that approved the bill. Quite the opposite: the new rules were sneaked into a bill that discussed subsidies to rural producers, with little or no room for debating their consequences. With the stroke of a pen, almost 1,300 lives were lost to violence in illegal mining sites.

We know that violence is not limited to illegal mining either. We should also be concerned about how legal mining is generating conflict. For example, it is known that mining companies sometimes establish relationships and make informal arrangements with armed groups in order to mine in areas controlled by the latter. One famous case is that of AngloGold Ashanti, a large, international mining company that made deals with a violent rebel group in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 2000’s, as described in a Human Rights Watch report.

Given such context, new public policies to boost the mining sector in Brazil are quite alarming. For example, the Projeto de Lei 191/2021 under debate in Congress allows for legal mining in Indigenous Territories. Moreover, Decrees 10.965/2022 and 10.966/2022 foster artisanal mining by both simplifying regulatory procedures in the ANM (National Mining Agency) and creating Pró-Mape (Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento da Mineração Artesanal e em Pequena Escala). By giving incentives to artisanal mining in the Amazon, these programs can have a grave social impact.

The reason to be particularly concerned with these new proposals is due to the speed with which they are being implemented. There has been little time to discuss the lack of governmental capacity to monitor the mining operations that already exist in the Amazon and their potential negative effects. Currently, there is a clear deficit in instruments to monitor, for instance, the origin of minerals or to determine whether miners are fulfilling social and environmental requirements.

Therefore, it is likely that the current proposals fostering the mining sector in the Amazon will not only boost violence, but also the complementarity between mining – legal or illegal – and criminal activities. Ultimately, many more will probably pay with their lives for the lack of serious debate about the curse that looms over promises of blessings.

Co-authored with Leila Pereira and Rafael Pucci