Amazon states have made good progress in the implementation of laws for protecting forests in private areas, but important challenges remain.

The Forest Code is Brazil’s key policy instrument for forest protection in private areas. In addition to establishing guidelines for the conservation and restoration of native vegetation in rural properties, the code defines rules that limit the conversion of forest areas for production inside these properties, thereby creating incentives for rural producers to invest in practices that result in productivity gains. By ensuring that Brazilian agricultural production complies with more rigorous environmental legislation, the Forest Code also promotes access to new markets for Brazilian products.

Yet, as Brazil nears the 10-year anniversary of the code’s enactment, implementing it remains a challenge. Although the Forest Code is a federal law, states are responsible for its implementation and therefore play a critical role in this process. In a recent study, researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/ PUC-Rio (CPI/PUC-Rio) provide an in-depth analysis of Brazilian states’ implementation of the Forest Code. Results indicate that states have made significant progress, particularly in the Amazon region.

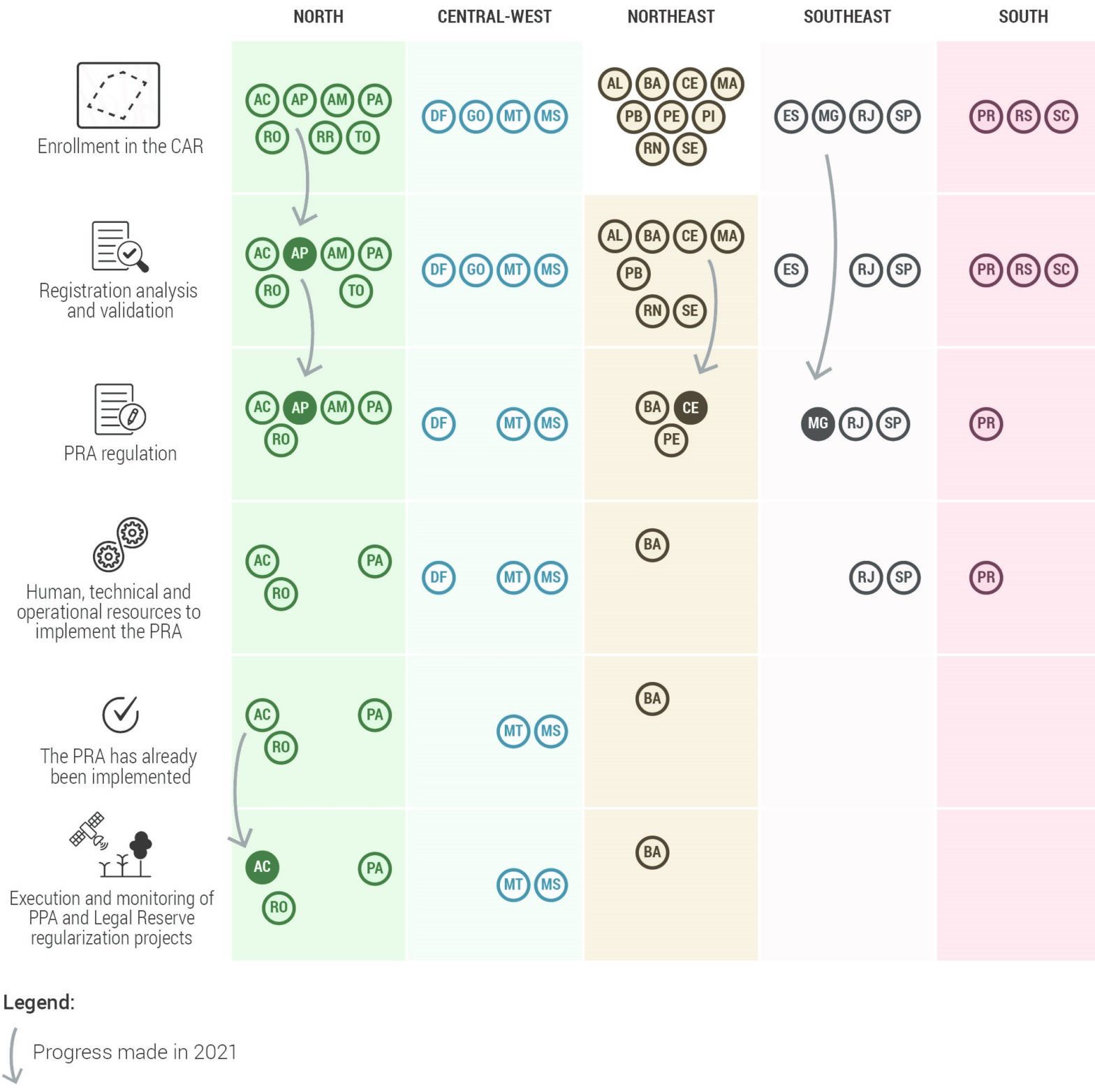

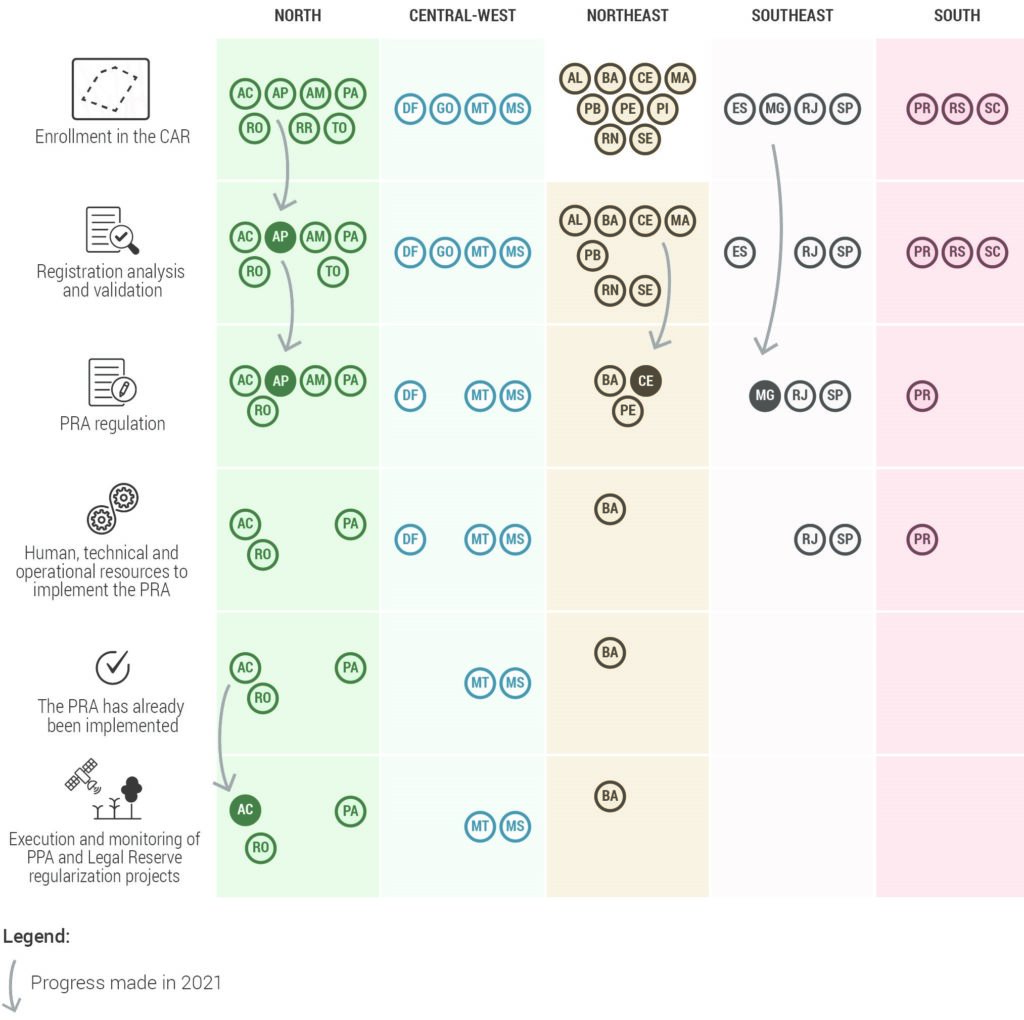

Compliance with the environmental requirements set forth by the code occurs in stages, including enrollment, analysis, and validation of the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR in the Portuguese acronym), as well as the regulation and implementation of the Environmental Compliance Program (PRA in the Portuguese acronym). CPI/PUC-Rio’s study finds that the states that are most advanced in Forest Code implementation — Acre, Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia — are all located inside the Amazon biome (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Status of CAR and PRA implementation at the state level, 2021

In absolute figures, Mato Grosso takes the lead, having started the analysis of over 51,000 registries, validated 6,158 registries, and signed 454 commitment agreements for environmental restoration inside private rural properties. However, Acre and Pará are the states that made the most progress in 2021. Acre saw a 48% increase in the number of properties enrolled in CAR, tripled the number of technical staff dedicated to analysis of enrolled properties, and increased the number of signed commitment agreements by 61%. In Pará, the number of analyzed registries rose by 272%, that of validated registries by 60%, and that of signed commitment agreements by 88%.

Although Pará ranks third in the number of agreements, the total area to be restored in Permanent Preservation Areas (APP in the Portuguese acronym) and Legal Reserves is three times larger than its equivalent in Mato Grosso, the state that leads in numbers of commitment agreements.

Rondônia’s effort to expand technical staff exclusively dedicated to the analysis and validation of CAR proved fruitful. The state currently has the capacity to analyze 1,700 entries per month, a rate that has been growing over time. Yet, Rondônia, like several other states, faces an important problem: a typical CAR entry must be analyzed an average of 14 times before being validated without inconsistencies. This has significantly delayed completion of the analysis stage. Maranhão has also made progress in 2021, having increased the number of validated registries by 700%.

One of the year’s key highlights refers to the adoption of the dynamic analysis module in Amapá and Amazonas, although implementation is still in its early stages. The tool was developed by the Brazilian Forestry Service to perform automatic checks and propose corrections to CAR registries. It has helped Amapá advance from the enrollment stage to analysis and validation stages of Forest Code implementation. Around 2,000 entries, a quarter of the state’s total, have already been checked under the module, which proposed automatic corrections to 1,800 of them. The corrected entries are currently awaiting approval from their respective owners.

Roraima, in contrast, is lagging behind. It belongs to a group of states that have no legislation for implementing the Forest Code, haven’t moved towards analyzing entries, don’t have cartographic layers needed for the dynamic analysis, and haven’t been included in technical and financial cooperation agreements. Available efforts and resources should be targeted at this group.

The Brazilian Forest Code has the potential to play a central role in promoting green growth, particularly in a post-pandemic context of economic recovery, by attracting financial resources that are aligned with conservation and forest restoration. To achieve this, however, Brazil must tackle the barriers that stand in the way of completing CAR analysis and validation, a key bottleneck for effective implementation of the forest law, and move towards the final stage of achieving environmental compliance regarding restoration in APPs and Legal Reserves.

Finally, there are many attempts to alter the Forest Code currently being proposed in the Brazilian National Congress. That is the case of PL nº 36/2021, which sets new deadlines for enrolling in CAR and preserving the right to adhere to PRA. It is critical that no alteration to the Forest Code be proposed without an in-depth analysis of its potential impacts on state’s implementation of the law. Legislative changes that require a significant revision of state rules will ultimately disregard the effort and resources that states have put into regulating and implementing these norms. Moreover, they will hinder the implementation of the Forest Code and the furthering of compliance with environmental regulation in rural private properties.

The opinions expressed in this article are the writer’s own.