The partnership promotes the integrated management of nine indigenous lands and three extractive reserves to ensure sustainability and preserve the forest.

The Initiative

- Name

- A Project that resumes the alliance between indigenous peoples and extractivist workers built in the 1980s by Chico Mendes.

- Who’s involved

- The Pro-Indian Commission of Acre (CPI-AC), SOS Amazônia, Catitu Institute, and community associations of extractivist workers and indigenous peoples.

- What is it

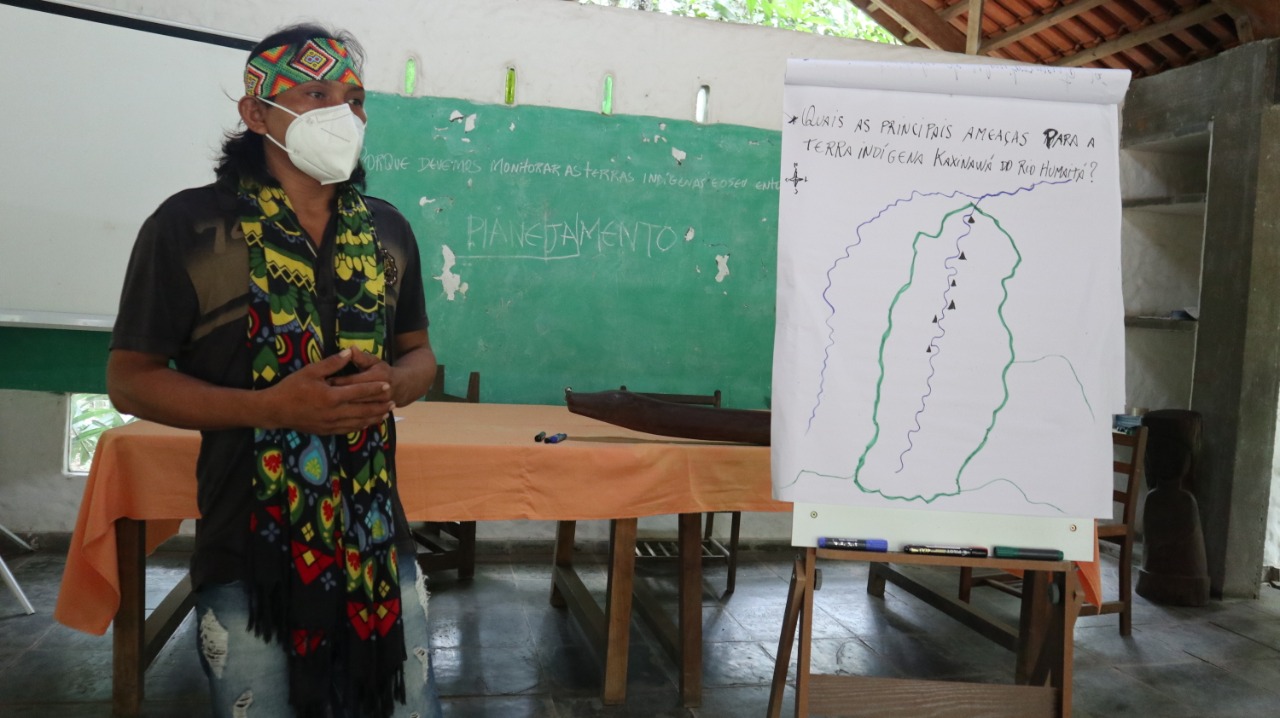

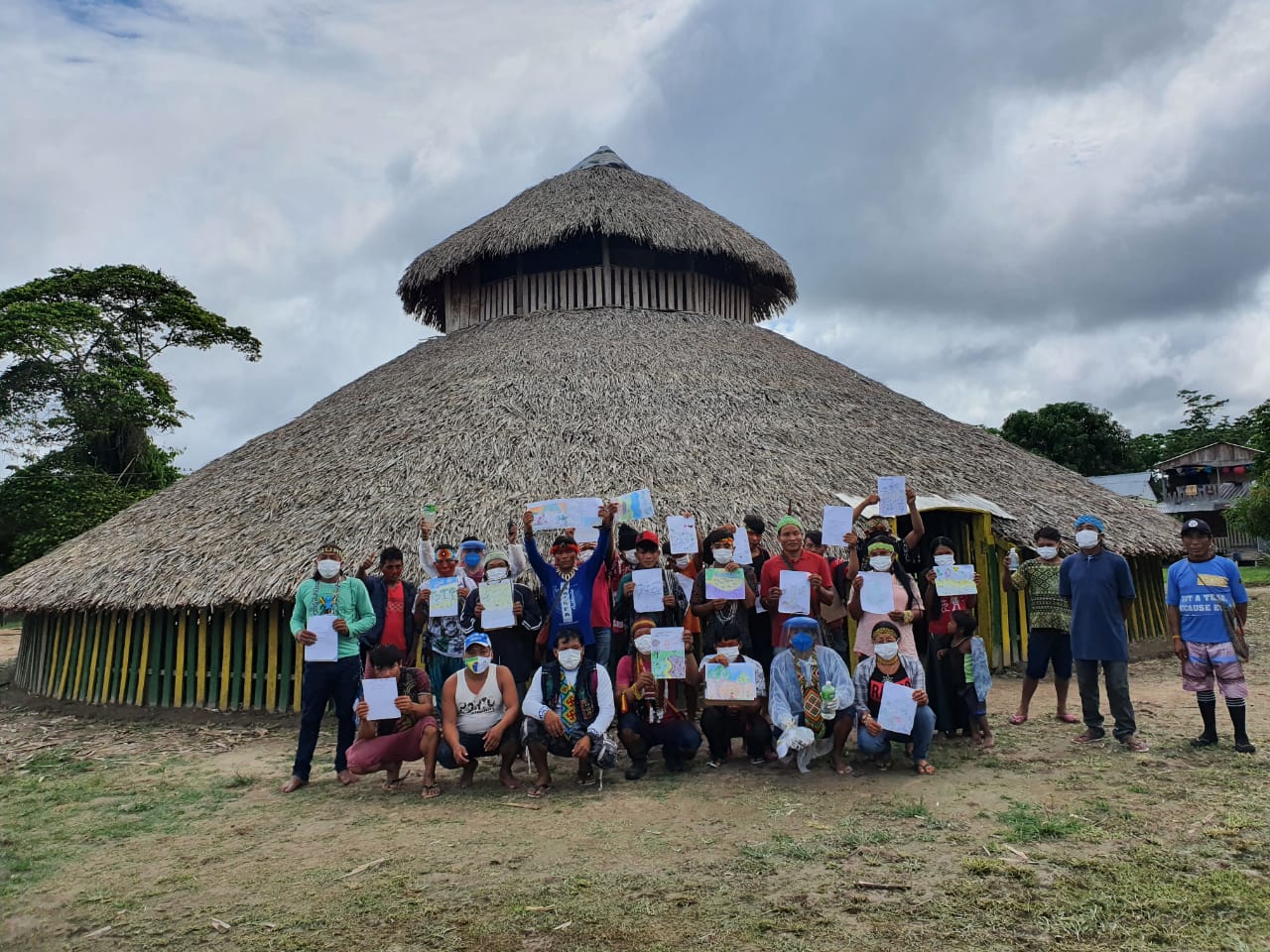

- It organizes meetings, courses, and workshops for the exchange of sustainable experiences and territorial monitoring.

- Where is it

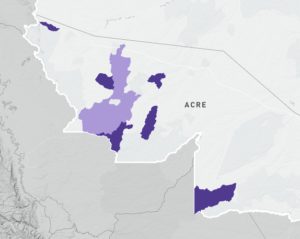

In the Kaxinawá do Baixo Rio Jordão, Kaxinawá do Rio Jordão, Kaxinawá do Seringal Independência, Kaxinawá do Rio Humaitá, Nukini, Mamoadate, Kaxinawá Praia do Carapanã, Arara do Igarapé Humaitá, Kaxinawá Ashaninka do Rio Breu Indigenous Lands, and in the Alto Juruá, Alto Tarauacá, and Riozinho da Liberdade extractive reserves, all located in Acre.

In the Kaxinawá do Baixo Rio Jordão, Kaxinawá do Rio Jordão, Kaxinawá do Seringal Independência, Kaxinawá do Rio Humaitá, Nukini, Mamoadate, Kaxinawá Praia do Carapanã, Arara do Igarapé Humaitá, Kaxinawá Ashaninka do Rio Breu Indigenous Lands, and in the Alto Juruá, Alto Tarauacá, and Riozinho da Liberdade extractive reserves, all located in Acre.

Created by indigenous people and rubber tappers in the 1980s to stop the advance of land grabbing and deforestation, the Alliance of Forest Peoples is being brought back in Acre by a project that aims to reconnect the two groups. Its aim aim is to deal with the region’s new challenges.

The “Alliance between indigenous peoples and extractivists for the forests of Acre” is being developed by three NGOs: the Pro-Indian Commission of Acre (CPI-AC), SOS Amazônia, and the Catitu Institute, which have joined with traditional populations to implement unprecedented integrated management of nine indigenous lands (TIs) and three extractive reserves (RESEX).

The areas represent 11.14% of the entire territory of Acre and house 11 thousand people, who are directly and indirectly responsible for protecting 17 thousand km² of forested lands, which guarantees their livelihood and the maintenance of their way of life.

The “Alliance” project began last year and is planning to carry out meetings, courses, and workshops by 2025 to exchange sustainable experiences and new forms of territorial protection and monitoring. The idea is also to respond to climate change and pressures from politics, the economy, and land invaders.

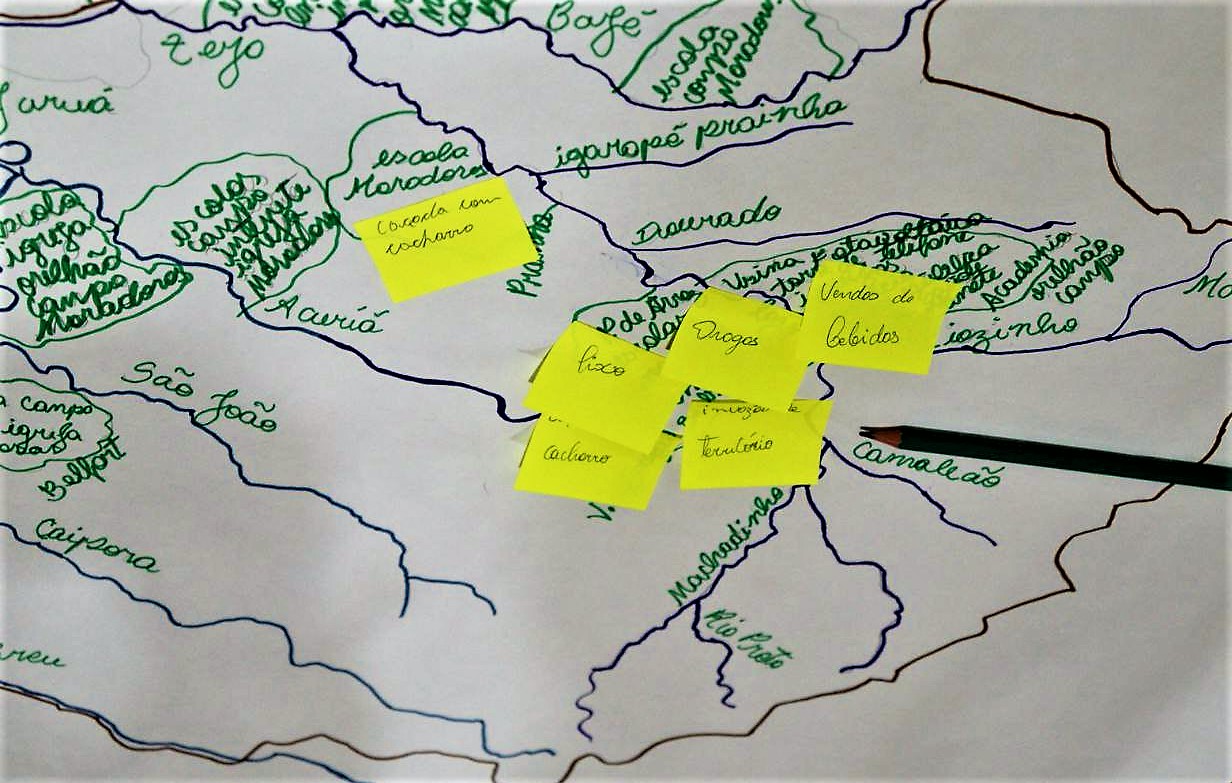

According to the CPI-AC, of the 34 indigenous lands demarcated in the state, 79% were invaded by hunters, 76% by fishermen, and 68% by loggers. The first was demarcated in 1984.

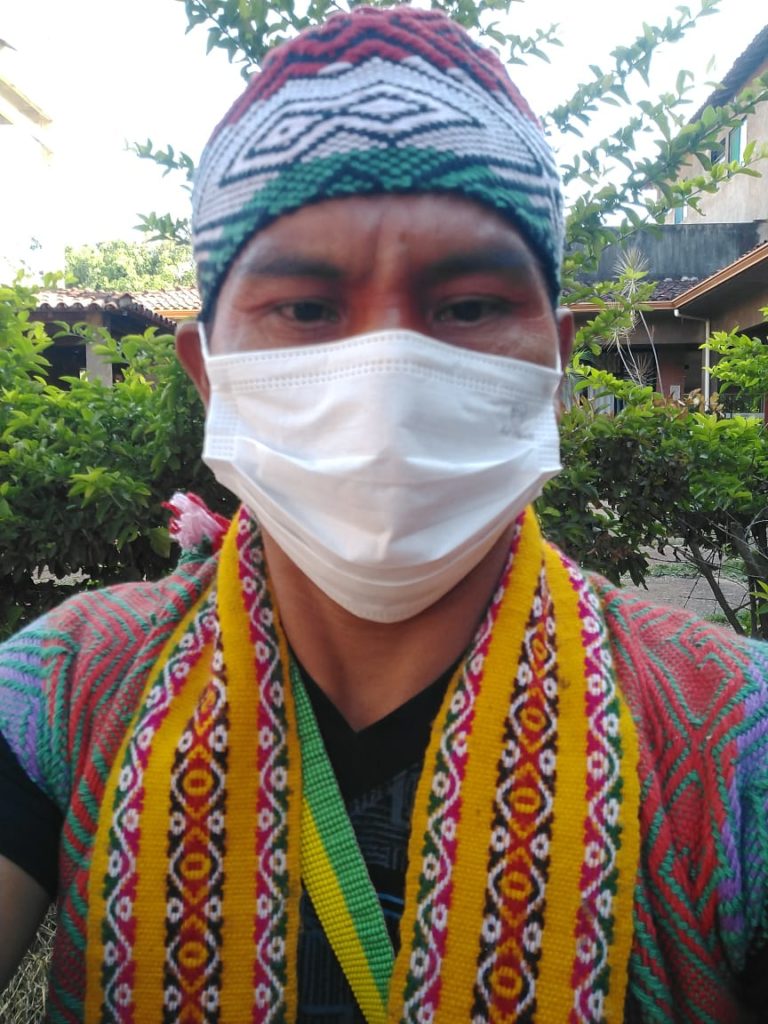

Last year, the Kaxinawá Indigenous Land of the Jordão River, on the Peruvian border, was invaded by loggers, and its leaders turned to the police for help. A suspect has been arrested. Agroforestry agent Josias Pereira Huni Kuin recalls the case:

“I’ve never seen so many trees felled in our land. They came in with a ferry to transport all the wood and we were threatened when we reported it”, said the member of the Huni Kuin people, whose grandfather and uncle were part of the historical alliance proposed in 1985 by environmentalist Chico Mendes, in the 1st National Meeting of Seringueiros (Rubber tappers), in Brasília.

“I’ve never seen so many trees felled in our land. They came in with a ferry to transport all the wood and we were threatened when we reported it”

Josias Pereira Huni Kuin, Agroforestry agent

To prevent these practices, the “Alliance” wants to strengthen the political organization community organizations in the region to influence decisions that guarantee not only territorial integrity but also the protection of springs and actions that reduce the effects of climate change, which already punishes local populations.

Taraucá, a Kaxinawá Indigenous Land in the Humaitá River, also a part of the project, suffered three floods this year alone. In one village, 1/3 of all agricultural goods were lost to the waters, and the people were forced to move their crops away from their homes.

Jocemir Saboia, one of the land’s leaders, is concerned about climate change and says that the time has come to react.: “We are already feeling a shock, and only unity will enable our protection. This is an alliance for our lives and the lives of animals and forests.”

The project also wants to recover deforested land and expand areas for family farming to achieve greater food security and financial wellbeing, from the sale of surplus goods.

“We are already feeling a shock, and only unity will enable our protection. This is an alliance for our lives and the lives of animals and forests”

Jocemir Saboia, Kaxinawá leader

Recovery of degraded areas

Another line of action seeks to stimulate the emergence of new leaders, especially in the Extractive Reserves, where the extractivist culture has been underappreciated by young people, weakening these groups’ identity. According to the SOS Amazônia Project Coordinator, Thayna Souza, the alliance bets on the empowerment of women and youth to reverse this trend:

“The idea is to adapt the context of the struggle of the 80s to the current reality, involving everyone, but focusing on young people and women, so that the identity and belonging of these groups are rescued, especially in the case of extractivist communities.”

Souza also points out that the political strengthening of communities wants to enable a joint struggle against a serious problem: precarious access to drinking water. The CPI-AC estimates that, between January and August 2019, 16 children died in a single indigenous land in the state due to diseases linked to water contamination.

José de Olinda Nobre is a 26-year-old teacher at the Alto Tarauacá Extractive Reserve, one of the three units of this type in the project. Born in the area, he is an active participant in the project and is a potential future leader.

“If the reserves didn’t exist, our parents, who were born here, would have lost their land, and the forests within would be devastated. Many young people do not understand this and I have sought to pass on this idea to keep the essence and principles of the Extractive Reserve alive.”

“The idea is to adapt the context of the struggle of the 80s to the current reality, involving everyone, but focusing on young people and women, so that the identity and belonging of these groups are rescued”

Thayna Souza, SOS Amazônia Project Coordinator

Vulnerable borders

Acre still has 85% of its forests standing, but has alarming deforestation rates. In 2021, it recorded the highest deforestation rate in the last decade, with 889 km² felled, according to the Deforestation Alert System (SAD) of the Amazon Institute of Man and Environment (Imazon). In addition, agribusiness-related development projects and infrastructure works, such as the opening of highways running over and around protected areas, impose even more pressure on forests and their populations.

The border region between Acre and Peru is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, and it is under threat by these initiatives on both sides of the border. The “Alliance” covers several territories in this border strip and acts resisting these projects.

“There is an important strategy in the region. The Alto Juruá Extractive Reserve, for example, is the first such experience in Brazil. There is also the Serra do Divisor National Park, which, despite not being in the project, is a protection unit that is part of our strategy, not to mention the indigenous lands, most of which are in the Juruá River Basin, in that border region, “explained the coordinator of the CPI-AC, Vera Olinda.

An alliance revisited

The classic Alliance of the Forest Peoples was a watershed in the socio-environmental struggle in the Amazon. In Acre, indigenous people and rubber tappers were enemies since the end of the 19th century, when rubber plantations started being implemented in the region. In the 1980s, in the context of the region’s predatory occupation, they realized they had opponents in common and decided to shake hands.

The alliance played a fundamental role in expanding the notion of environmental conservation in force at the time, which underestimated the importance of traditional populations for protecting the environment. The exchange of experiences between the two groups helped shape the concept of Extractive Reserves, inspired by the older indigenous lands. The Alliance also led to change in indigenous policy towards isolated peoples.

“The children, grandchildren, and nephews of the indigenous people and rubber tappers who joined the Alliance in the past are now taking back the struggle. The current challenge is to unite so as not to lose everything we have achieved, without taking our eyes off the future,” concludes Huni Kuin leader Josias Pereira.

How to get involved

- Contact information

- institucional@cpiacre.org.br

ascom@cpiacre.org.br