We need to evaluate government speeches and policies based on what really needs to be done in the face of the climate crisis.

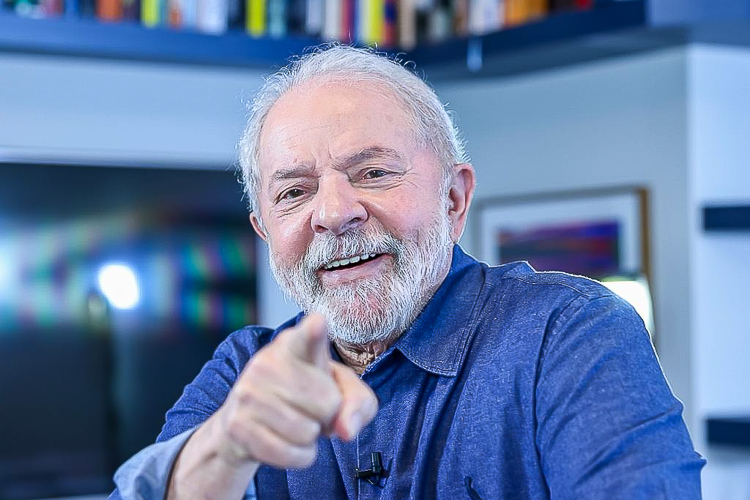

“Now, we will fight for zero deforestation of the Amazon.” This phrase was in Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s first pronouncement after his election as president was confirmed. Such words comfort the yearnings of many, like me, who work for conservation in the Amazon. They reinforce the expectation that Brazil will again set an example to the world on how to act to avoid the worsening of the climate crisis. Moreover, this sentence automatically raises the bar to evaluate governmental climate policies and actions. May the times of settling for low climate ambition speeches be in the past!

The climate crisis is not just knocking on our door. It is hitting us in the face! In 2022, there were at least four major examples of extreme weather events in the country: floods and tragedy in Bahia, in Petrópolis, in Recife, and more recently a historic drought in the Amazon. There have been deaths and losses for thousands of Brazilian families. And such situations were not enough for governments in the country to create programs of adaptation to such extreme events.

President-elect Lula’s opening words signaled that dealing with the climate crisis is on the agenda for his next term. But it will not be enough to wait for the federal government to rebuild environmental policies that have been undone by the Bolsonaro government. We also need to demand from the states that they align their policies and incentives to more expressively and quickly reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil. After all, environmental management is shared between the different levels of government.

Despite of the alliances of state governments that have emerged in the last few years with the purpose of stopping the federal anti-environmental policies, there have been no significant results. In the Amazon, deforestation continued to rise.

“Despite of the alliances of state governments that have emerged in the last few years with the purpose of stopping the federal anti-environmental policies, there have been no significant results. In the Amazon, deforestation continued to rise”.

Brenda Brito

The state alliances on the environmental agenda without support from the federal government were limited by at least two aspects. First, the actors involved in deforestation, mining and other environmental crimes are part of the political base of many of these governments. Second, there are structural factors of environmental governance in Brazil that limit the practical capacity of the states on the issue. For example, the environmental management duty is shared between the federal, state and municipal governments, but there is no transfer of resources to guarantee these functions in a decentralized manner.

However, the absence of a budget transfer does not justify political decisions by these state governments that are misaligned with environmental conservation. For example, the governor of Rondônia sanction of the law that reduced almost 220 thousand hectares of state protected areas, which fortunately was suspended in November 2021 by the judiciary. In another recent case, the governor of Roraima sanctioned a state law that contradicts the federal constitution by prohibiting the destruction of machinery used in environmental crimes. In Pará, a 2020 state decree could allocate a state subsidy of R$6.7 billion in the eventual sale of public land, which reinforces a perverse incentive for illegal occupation and speculation of public lands.

Considering the severity of the climate crisis and the upcoming change in the federal government, we need to collectively raise the bar in assessing climate policies in Brazil. The next four years will be key for Brazil to establish policies and actions with the necessary climate ambition according to science. And zero deforestation by 2030 needs to be a major collective goal to be pursued at all levels of government.

To expand support for this goal, we may need to find “climate Janones” who can bring the message of climate urgency more attractively to more and more people. We have many lessons about communication to learn from Federal Congressman André Janones, who fought fake news and engaged millions of people on social networks in Lula’s campaign.

After all, the degree of awareness and demand we have now regarding climate policies will determine the future our children will have. That is, if they will suffer with the scenarios of greater global warming or if they will be able to deal in a less traumatic way with the already inevitable climate effects.