While most consumers in Brazil are interconnected and fueled by renewable energy, many in the Amazon are isolated and rely on fossil fuels. We all foot that bill.

The Amazon plays a key role in Brazil’s production of renewable electric energy. Home to four of the country’s five largest hydroelectric power plants, the region helps ensure that renewables account for 82% of electricity produced nationally. According to the International Energy Agency, the global average is only 27%.

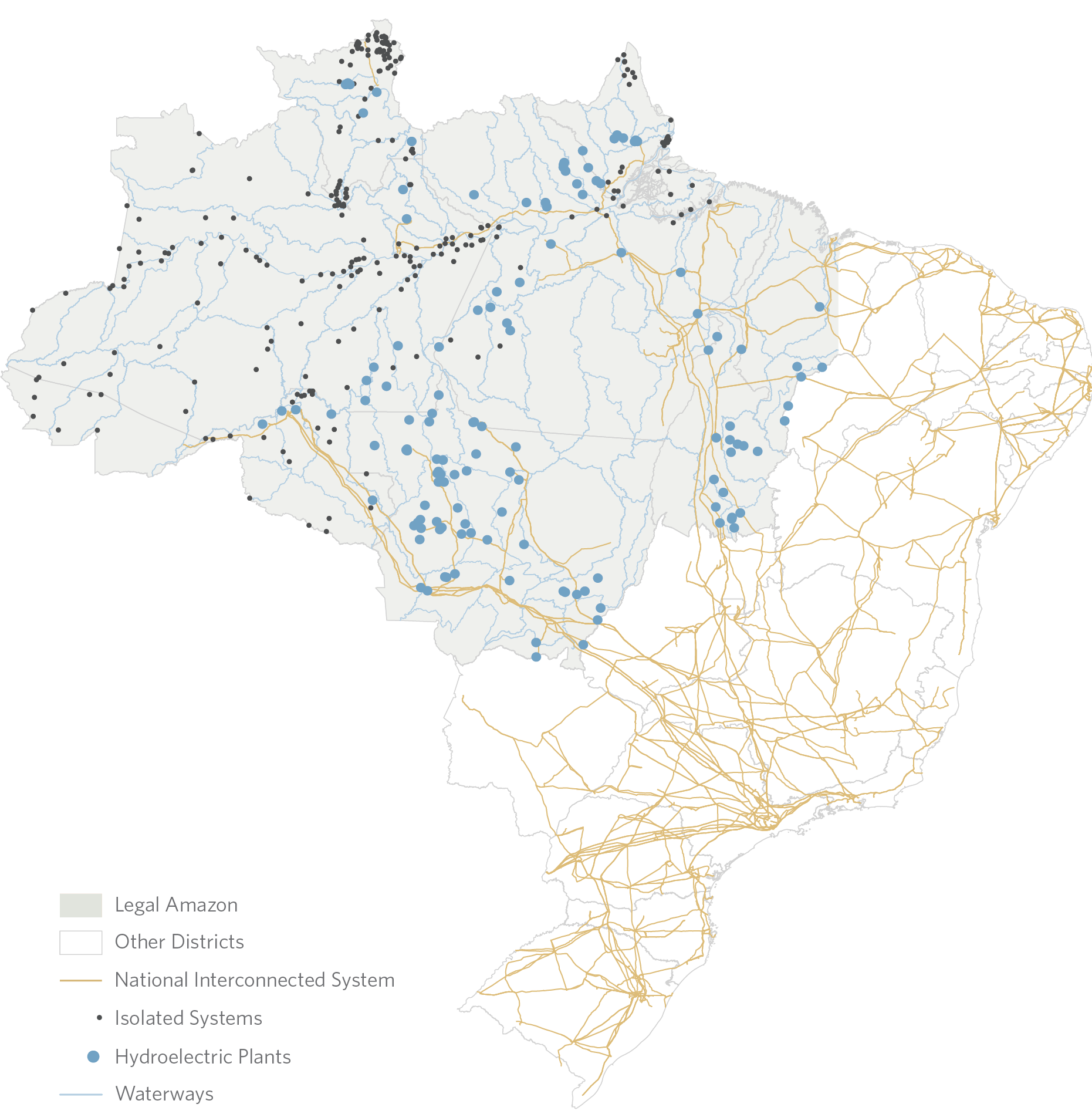

Although it exports renewable energy to the rest of the country, the Amazon still uses fossil fuels, which are both highly polluting and expensive, to meet part of its local demand for electricity. In 2020, the region accounted for more than 26% of the electricity produced in Brazil, but consumed only 8% of it. There are 4 million people, or 14% of its population, who are not part of the National Interconnected System (SIN in the Portuguese acronym).

SIN uses transmission lines to connect power plants throughout the country and carry the energy produced in these power plants to consumers across Brazil. The system protects inhabitants of a given region from interruptions in energy supply. If production by the local plant is interrupted due to operational or weather conditions, like rainfall in areas with hydroelectric plants, the needs of consumers who are connected to the SIN can be met using energy produced in other regions.

There are, however, about 3 million people in the Amazon who are not connected to the SIN and who consume energy produced in local power plants. More than 95% of their electricity comes from thermoelectric power plants fueled by diesel, in the so-called “isolated systems”.

These systems are found in remote places as well as urban centers, and they serve populations that vary substantially in size and demand for energy. The capital of the state of Roraima, for example, is not connected to the SIN.

There are also nearly 1 million people in the Amazon who do not have continuous access to electricity. Relying on generators fueled by diesel or gasoline, they can count on having only a few hours of electricity per day.

Hydroelectric Power Plants and Transmission Lines in the National Interconnected System

It’s worth noting that there already are SIN transmission lines in the Brazilian Amazon connecting the hydroelectric power plants and part of the population. Yet, environmental, logistic, and economic issues are often cited as barriers to the extension of these lines. Ironically, some of the communities that either depend on isolated systems or have no access to electricity are found quite close to hydroelectric power plants.

This has relevant socioeconomic and environmental implications. Fossil fuel-based isolated systems are extremely polluting. Although they account for only 0,6% of the energy consumed in Brazil, total greenhouse gas emissions from these systems amount to nearly 10% of the SIN’s emissions. In addition, there are emissions associated with transporting diesel to the power plants and generators. Transportation, which is typically made via rivers or roads, faces significant logistic challenges.

There are emissions associated with transporting diesel to the power plants and generators. Transportation, which is typically made via rivers or roads, faces significant logistic challenges.

Generating electricity in isolated systems is also very expensive, both because it uses diesel as fuel and because it entails operations at smaller scales. For 2022, the Brazilian Energy Research Office estimates the additional cost of generating energy in thermal isolated systems at over BRL 10 billion, as compared to generating the same amount in the SIN. This is currently equivalent to an annual per capita subsidy of more than BRL 3 thousand per consumer in the isolated systems. With rising diesel prices, this figure is bound to increase.

The people in the Amazon are not the only ones who bear the financial burden of the current setup. Every consumer of electricity in Brazil pays for it as well, since electricity bills countrywide are adjusted to cover these costs.

Moreover, access to electricity is closely related to regional development. Municipalities with isolated systems perform worse across several socioeconomic indicators than those that are connected to the SIN, considering both the regional average and state-specific averages.

The poor supply of energy in isolated systems harms the local economy, interfering with industrial activity, commerce, and services. Connecting a region to the SIN improves the quality and reliability of electricity supply.

The situation is even more dramatic for those who have access to neither the SIN nor isolated systems. Without energy, these people cannot have many of their basic needs met. They often face highly challenging conditions for health, education, communications, territorial defense, and production.

The situation is even more dramatic for those who have access to neither the SIN nor isolated systems. Without energy, these people cannot have many of their basic needs met.

Refrigerating food and medication, ensuring connectivity and access to means of communication, nighttime lighting, and pumping water are only a few of a vast amount of activities that fundamentally depend on electricity. Electricity is also a key input for developing sectors that promote sustainable production, including those that add value to standing forests. Without it, local populations are often forced to use the available resources unsustainably.

A recent study by Climate Policy Initiative / PUC-Rio brings recommendations to mitigate this scenario. Researchers note it is important to create enabling conditions for renewables-based initiatives to compete in the auctions as suppliers to isolated systems. They also stress that decentralized solar generation could be used to meet the demand of those who are currently relying on isolated systems or have no access to electricity in the Amazon. Finally, authors suggest improving the “Mais Luz para a Amazônia” program by creating objective targets, implementing transparent prioritization criteria, adopting effective monitoring, and enabling the direct involvement of local communities.

Promoting the energy transition in the Brazilian Amazon is not only critical, but also widely beneficial. It generates environmental gains, improves the quality of life of those living in the region, and reduces the electricity bill for all Brazilians. It’s not reasonable to depend on highly polluting and expensive fuels to generate electricity in the Amazon.

The opinion articles are the author’s own responsibility.